|

|

The TComponent ClassIf the TPersistent class is more important than it seems at first sight, the key class at the heart of Delphi's component-based class library is TComponent, which inherits from TPersistent (and from TObject). The TComponent class defines many core elements of components; however, it is not as complex as you might think, because the base classes and the language already provide most of what's needed. I won't explore all the details of the TComponent class, some of which are more important for component designers than they are for component users. I'll just discuss ownership (which accounts for some public properties of the class) and the two published properties of the class, Name and Tag. OwnershipOne of the core features of the TComponent class is the definition of ownership. When a component is created, it can be assigned an owner component, which will be responsible for destroying it. So, every component can have an owner and can also be the owner of other components. Several public methods and properties of the class are devoted to handling the two sides of ownership. Here is a list, extracted from the class declaration (in the Classes unit of the VCL):

type

TComponent = class(TPersistent, IInterface, IInterfaceComponentReference)

public

constructor Create(AOwner: TComponent); virtual;

procedure DestroyComponents;

function FindComponent(const AName: string): TComponent;

procedure InsertComponent(AComponent: TComponent);

procedure RemoveComponent(AComponent: TComponent);

property Components[Index: Integer]: TComponent read GetComponent;

property ComponentCount: Integer read GetComponentCount;

property ComponentIndex: Integer

read GetComponentIndex write SetComponentIndex;

property Owner: TComponent read FOwner;

If you create a component and give it an owner, it will be added to the list of components (InsertComponent), which is accessible using the Components array property. The specific component has an Owner and knows its position in the owner components list, with the ComponentIndex property. Finally, the owner's destructor will take care of the destruction of the object it owns by calling DestroyComponents. A few more protected methods are involved, but this should give you the overall picture. It's important to emphasize that component ownership can solve many of your applications' memory management problems, if used properly. When you use the Form Designer or Data Module Designer of the IDE, that form or data module will own any component dropped on it. At the same time, you should generally create components with a form or data module owner, even in your code. In these circumstances you only need to remember to destroy the component containers (form or data module) when they are not needed anymore, and you can forget about the components they contain. For example, you delete a form to destroy all the components it contains at once, which is a major simplification compared to having to remember to free each and every object individually. At a larger scale, forms and data modules are generally owned by the Application object, which is destroyed by the VCL shutdown code freeing all of the component containers, which free the components they contain. The Components ArrayThe Components property can also be used to access one component owned by another—let's say, a form. This property can be very handy (compared to using a specific component directly) for writing generic code, acting on all or many components at a time. For example, you can use the following code to add to a list box the names of all a form's components (this code is part of the ChangeOwner example presented in the next section):

procedure TForm1.Button1Click(Sender: TObject);

var

I: Integer;

begin

ListBox1.Items.Clear;

for I := 0 to ComponentCount - 1 do

ListBox1.Items.Add (Components [I].Name);

end;

This code uses the ComponentCount property, which holds the total number of components owned by the current form, and the Components property, which is the list of owned components. When you access a value from this list, you get a value of the TComponent type. For this reason, you can directly use only the properties common to all components, such as the Name property. To use properties specific to particular components, you have to use the proper type-downcast (as).

Using the Components property, you can always access each component of a form. If you need access to a specific component, however, instead of comparing each name with the name of the component you are looking for, you can let Delphi do this work by using the form's FindComponent method. This method simply scans the Components array looking for a name match. More information about the role of the Name property for a component is in the section "The Name Property." Changing the OwnerYou have seen that almost every component has an owner. When a component is created at design time (or from the resulting DFM file), its owner will invariably be its form. When you create a component at run time, the owner is passed as a parameter to the Create constructor. Owner is a read-only property, so you cannot change it. The owner is set at creation time and should generally not change during the lifetime of a component. To understand why you should not change a component's owner at design time nor freely change its name, read the following discussion. Be warned that the topic covered is not simple; if you're just beginning with Delphi, you might want to come back to this section at a later time. To change the owner of a component, you can call the InsertComponent and RemoveComponent methods of the owner itself, passing the current component as parameter. However, you cannot apply these methods directly in a form's event handler, as I attempt to do here: procedure TForm1.Button1Click(Sender: TObject); begin RemoveComponent (Button1); Form2.InsertComponent (Button1); end; This code produces a memory access violation, because when you call RemoveComponent, Delphi disconnects the component from the form field (Button1), setting it to nil. (I talk more about form fields in the section "Removing Form Fields.") The solution is to write a procedure like this: procedure ChangeOwner (Component, NewOwner: TComponent); begin Component.Owner.RemoveComponent (Component); NewOwner.InsertComponent (Component); end; This method (extracted from the ChangeOwner example) changes the owner of the component. It is called along with the simpler code used to change the parent component; the two commands combined move the button completely to another form, changing its owner:

procedure TForm1.ButtonChangeClick(Sender: TObject);

begin

if Assigned (Button1) then

begin

// change parent

Button1.Parent := Form2;

// change owner

ChangeOwner (Button1, Form2);

end;

end;

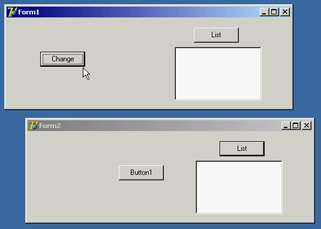

The method checks whether the Button1 field still refers to the control, because while moving the component, Delphi will set Button1 to nil. You can see the effect of this code in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3: In the ChangeOwner example, clicking the Change button moves the Button1 component to the second form. To demonstrate that the owner of the Button1 component actually changes, I've added another feature to both forms. The List button fills the list box with the names of the components each form owns, using the procedure shown in the previous section. Click the two List buttons before and after moving the component, and you'll see what happens behind the scenes. As a final feature, the Button1 component has a simple handler for its OnClick event, to display the caption of the owner form: The Name PropertyEvery component in Delphi should have a name. The name must be unique within the owner component, which is generally the form into which you place the component. This means an application can have two different forms, each with a component that has the same name, although you might want to avoid this practice to prevent confusion. It is generally better to keep component names unique throughout an application. Setting a proper value for the Name property is very important: If it's too long, you'll need to type a lot of code to use the object; if it's too short, you may confuse different objects. Usually the name of a component has a prefix with the component type; this makes the code more readable and allows Delphi to group components in the combo box of the Object Inspector, where they are sorted by name. Three important elements are related to a component's Name property:

As mentioned earlier, if you have a string with the name of a component, you can get its instance by calling the FindComponent method of its owner, which returns nil if the component is not found. For example, you can write

var

Comp: TComponent;

begin

Comp := FindComponent ('Button1');

if Assigned (Comp) then

with Comp as TButton do

// some code...

Removing Form FieldsEvery time you add a component to a form, Delphi adds an entry for it, along with some of its properties, to the DFM file. To the Pascal file, Delphi adds the corresponding field in the form class declaration. This field of the form is a reference to the corresponding object, as is any class-type variable in Delphi. When the form is created, Delphi loads the DFM file and uses it to re-create all the components and set their properties back to the design-time values, saved in the DFM file itself. Then it connects the new object with the form field corresponding to its Name property. This is why in your code, you can use the form field to operate on the corresponding component. For this reason, it is possible to have a component without a name. If your application will not manipulate the component or modify it at run time, you can remove the component name from the Object Inspector. Examples include a static label with fixed text, or a menu item, or even more obviously, menu item separators. By blanking out the name, you remove the corresponding element from the form class declaration. Doing so reduces the size of the form object (by only four bytes, the size of the object reference) and reduces the DFM file by not including a useless string (the component name). Reducing the DFM file size also implies reducing the final executable file size, even if only slightly.

You can also keep the component name and manually remove the corresponding field of the form class. Even if the component has no corresponding form field, it is created anyway, although using it (through the FindComponent method, for example) will be a little more difficult. Hiding Form FieldsMany OOP purists complain that Delphi doesn't really follow the encapsulation rules, because all the components of a form are mapped to public fields and can be accessed from other forms and units. Fields for components are listed in the first unnamed section of a class declaration, which has a default visibility of published. However, Delphi does that only as a default to help beginners learn to use the Delphi visual development environment quickly. A programmer can follow a different approach and use properties and methods to operate on forms. The risk, however, is that another programmer on the same team might inadvertently bypass this approach, directly accessing the components if they are left in the published section. The solution, which many programmers don't know about, is to move the components to the private portion of the class declaration. As an example, I've made a simple form with an edit box, a button, and a list box. When the edit box contains text and the user clicks the button, the text is added to the list box. When the edit box is empty, the button is disabled. This is the code of the HideComp example: procedure TForm1.Button1Click(Sender: TObject); begin ListBox1.Items.Add (Edit1.Text); end; procedure TForm1.Edit1Change(Sender: TObject); begin Button1.Enabled := Length (Edit1.Text) <> 0; end; I've listed these methods only to show you that in a form's code, you usually refer to the available components, defining their interactions. For this reason, it seems impossible to get rid of the fields corresponding to the component. However, you can hide them, moving them from the default published section to the private section of the form class declaration: TForm1 = class(TForm) procedure Button1Click(Sender: TObject); procedure Edit1Change(Sender: TObject); procedure FormCreate(Sender: TObject); private Button1: TButton; Edit1: TEdit; ListBox1: TListBox; end; Now, if you run the program you'll get in trouble: The form will load, but because the private fields are not initialized, the events will use nil object references. Delphi usually initializes the published fields of the form using the components created from the DFM file. What if you do it yourself, with the following code?

procedure TForm1.FormCreate(Sender: TObject);

begin

Button1 := FindComponent ('Button1') as TButton;

Edit1 := FindComponent ('Edit1') as TEdit;

ListBox1 := FindComponent ('ListBox1') as TListBox;

end;

It will almost work, but it generates a system error, similar to the one discussed in the previous section. This time, the private declarations will cause the linker to link in the implementations of those classes; the problem is, the streaming system needs to know the names of the classes in order to locate the class reference needed to construct the components while loading the DFM file. The final touch you need is registration code to tell Delphi at run time about the existence of the component classes you want to use. You should do this before the form is created, so I generally place this code in the initialization section of the unit: initialization RegisterClasses ([TButton, TEdit, TListBox]); The question is, is this really worth the effort? You obtain a higher degree of encapsulation, protecting the components of a form from other forms (and other programmers writing them). Replicating these steps for every form can be tedious, so I wrote a wizard to generate the code for me on the fly. The wizard is far from perfect, because it doesn't handle changes automatically, but it is usable. See Appendix A, "Extra Delphi Tools by the Author," for more information about how to get it. For a large project built according to the principles of object-oriented programming, I recommend you consider this or a similar technique. The Customizable Tag PropertyThe Tag property is strange, because it has no effect at all. It is merely an extra memory location, present in each component class, where you can store custom values. The kind of information stored and the way it is used are completely up to you. It is often useful to have an extra memory location to attach information to a component without needing to define it in your component class. Technically, the Tag property stores a long integer so that, for example, you can store the entry number of an array or list that corresponds to an object. Using typecasting, you can store in the Tag property a pointer, an object reference, or anything else that is four bytes wide. A programmer can associate virtually anything with a component using its tag. You'll see how to use this property in several examples in future chapters. EventsNow that I've discussed the TComponent class, I need to introduce one more element of Delphi. Delphi components are programmed using PME: properties, methods, and events. Methods and properties should be clear by now, but you haven't yet learned about events. The reason is that events don't imply a new language feature but are simply a standard coding technique. An event is technically a property—the only difference is that it refers to a method (a method pointer type, to be precise) instead of other types of data. Events in DelphiWhen a user does something with a component, such as click it, the component generates an event. Other events are generated by the system, in response to a method call or a change to one of that component's properties (or even a different component's). For example, if you set the focus on a component, the component currently having the focus loses it, triggering the corresponding event. Technically, most Delphi events are triggered when a corresponding operating system message is received, although the events do not match the messages on a one-to-one basis. Delphi events tend to be higher-level than operating system messages, and Delphi provides a number of extra inter-component messages. From a theoretical point of view, an event is the result of a request sent to a component or control, which can respond to the message. Following this approach, to handle the click event of a button, you would need to subclass the TButton class and add the new event handler code inside the new class. In practice, creating a new class for every component you want to use is too complex to be a reasonable solution. In Delphi, a component's event handler usually is a method of the form that holds the component, not of the component itself. In other words, the component relies on its owner, the form, to handle its events. This technique is called delegation, and it is fundamental to the Delphi component-based model. This way, you don't have to modify the TButton class, unless you want to define a new type of component, but can simply customize its owner to modify the behavior of the button.

Method PointersEvents rely on a specific feature of the Delphi language: method pointers. A method pointer type is like a procedural type, but one that refers to a method. Technically, a method pointer type is a procedural type that has an implicit Self parameter. In other words, a variable of a procedural type stores the address of a function to call, provided it has a given set of parameters. A method pointer variable stores two addresses: the address of the method code and the address of an object instance (data). The address of the object instance will show up as Self inside the method body when the method code is called using this method pointer.

The declaration of a method pointer type is similar to that of a procedural type, except that it has the keywords of object at the end of the declaration: type IntProceduralType = procedure (Num: Integer); IntMethodPointerType = procedure (Num: Integer) of object; When you have declared such a method pointer type, you can declare a variable of this type and assign to it a compatible method—a method that has the same signature (parameters, return type, calling convention)—of another object. When you add an OnClick event handler for a button, Delphi does exactly that. The button has a method pointer type property, named OnClick, and you can directly or indirectly assign to it a method of another object, such as a form. When a user clicks the button, this method is executed, even if you have defined it inside another class. What follows is a sketch of the code Delphi uses to define the event handler of a button component and the related method of a form:

type

TNotifyEvent = procedure (Sender: TObject) of object;

MyButton = class

OnClick: TNotifyEvent;

end;

TForm1 = class (TForm)

procedure Button1Click (Sender: TObject);

Button1: MyButton;

end;

var

Form1: TForm1;

Now, inside a procedure, you can write MyButton.OnClick := Form1.Button1Click; The only real difference between this code fragment and the VCL code is that OnClick is a property name, and the data it refers to is called FOnClick. An event that shows up in the Events page of the Object Inspector is nothing more than a property of a method pointer type. This means, for example, that you can dynamically modify the event handler attached to a component at design time or even build a new component at run time and assign an event handler to it. Events Are PropertiesI've already mentioned that events are properties. To handle an event of a component, you assign a method to the corresponding event property. When you double-click an event value in the Object Inspector, a new method is added to the owner form and assigned to the proper event property of the component. It is possible for several events to share the same event handler or change an event handler at run time. To use this feature, you don't need much knowledge of the language. In fact, when you select an event in the Object Inspector, you can click the arrow button to the right of the event name to see a drop-down list of compatible methods—methods having the same signature of the method pointer type. Using the Object Inspector, it is easy to select the same method for the same event of different components or for different, compatible events of the same component. Just as you added some properties to the TDate class in Chapter 2, you can add one event. The event will be very simple. It will be called OnChange, and it can be used to warn the user of the component that the date value has changed. To define an event, you simply define a property corresponding to it and add some data to store the method pointer the event refers to. These are the new definitions added to the class, available in the DateEvt example:

type

TDate = class

private

FOnChange: TNotifyEvent;

...

protected

procedure DoChange; dynamic;

...

public

property OnChange: TNotifyEvent

read FOnChange write FOnChange;

...

end;

The property definition is simple. A user of this class can assign a new value to the property and, hence, to the FOnChange private field. The class doesn't assign a value to this FOnChange field; the user of the component does the assignment. The TDate class simply calls the method stored in the FOnChange field when the value of the date changes. Of course, the call takes place only if the event property has been assigned. The DoChange method (declared as a dynamic method as is traditional with event-firing methods) makes the test and the method call:

procedure TDate.DoChange;

begin

if Assigned (FOnChange) then

FOnChange (Self);

end;

The DoChange method in turn is called every time one of the values changes, as in the following method: procedure TDate.SetValue (y, m, d: Integer); begin fDate := EncodeDate (y, m, d); // fire the event DoChange; If you look at the program that uses this class, you can simplify its code considerably. First, add a new custom method to the form class:

type

TDateForm = class(TForm)

...

procedure DateChange(Sender: TObject);

The method's code simply updates the label with the current value of the TDate object's Text property: procedure TDateForm.DateChange; begin LabelDate.Caption := TheDay.Text; end; This event handler is then installed in the FormCreate method: procedure TDateForm.FormCreate(Sender: TObject); begin TheDay := TDate.Init (2003, 7, 4); LabelDate.Caption := TheDay.Text; // assign the event handler for future changes TheDay.OnChange := DateChange; end; This seems like a lot of work. Was I lying when I told you the event handler would save you some coding? No. Now, after you've added some code, you can forget about updating the label when you change some of the object data. For example, here is the handler of the OnClick event of one of the buttons: procedure TDateForm.BtnIncreaseClick(Sender: TObject); begin TheDay.Increase; end; The same simplified code is present in many other event handlers. Once you have installed the event handler, you don't have to remember to update the label continually. That eliminates a significant potential source of errors in the program. Also note that you had to write some code at the beginning because this is not a component installed in Delphi but simply a class. With a component, you select the event handler in the Object Inspector and write a single line of code to update the label—that's all.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copyright © 2004-2024 "Delphi Sources" by BrokenByte Software. Delphi Programming Guide |